Plaza de Fundación

Audio Tour

On that fateful night on May 5th, 1718, the stars that they saw and the expansive night sky were a reminder of the great frontier that they were discovering. The sky was their limit and the potential was infinite.

Here at the Plaza de Fundación, very near the first location of Mission San Antonio de Valero (now known as the Alamo), the heavens and the earth unite as water cascades over a screen depicting that exact night sky from 1718. As darkness falls over the Plaza de Fundación, the place of the city and county’s founding, the stars glisten in the falling water in a vivid demonstration of the cosmic bond that links generations across time and space.

Before you you’ll see twelve Generational Benches. These benches honor the twelve generations of pioneers, entrepreneurs, soldiers, and visionaries that have shaped the community since its founding in 1718.

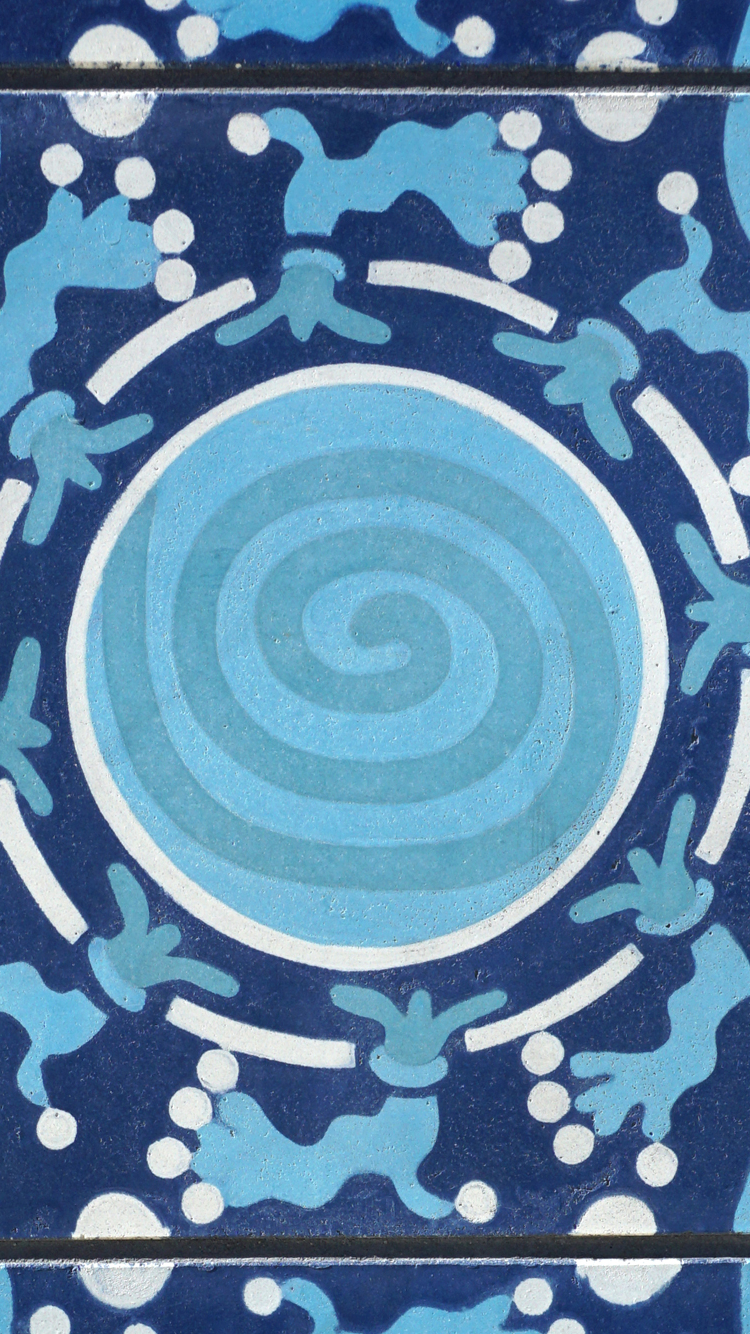

Each bench is adorned with colorful tiles designed by artist Michael Menchaca. Used throughout the park, the tiles are based on the long tradition of Mexican Talavera tile work and draw inspiration from pictorial history books of ancient Mesoamerica.

Menchaca has a Master of Fine Art in Printmaking from the Rhode Island School of Design. He exhibits all over the country and has participated in artist residencies across the globe.

Audio Guía

En esa fatídica noche del 5 de mayo de 1718, las estrellas que vieron y el vasto cielo nocturno fueron un indicio de la gran frontera que estaban descubriendo. El cielo era su límite y el potencial era infinito.

Aquí en la Plaza de la Fundación, muy cerca de la primera sede de la Misión de San Antonio de Valero (ahora conocida como el Álamo), los cielos y la tierra se unen como cascadas de agua sobre una pantalla que representa exactamente aquel cielo nocturno de 1718. A medida que la oscuridad cae sobre la Plaza de la Fundación, el lugar donde se fundaron la ciudad y el condado, las estrellas brillan en el agua que cae, como una vívida demostración del vínculo cósmico que une a las generaciones a través del tiempo y el espacio.

Ahora usted puede ver las doce Bancas Generacionales. Estas bancas honran a las doce generaciones de pioneros, empresarios, soldados y visionarios que han moldeado a la comunidad desde su fundación en 1718. Cada banca está adornada con azulejos de gran colorido diseñados por el artista Michael Menchaca. Instaladas en todo el parque, sus azulejos se basan en la larga tradición del trabajo de azulejos mexicanos de Talavera y se inspiraron en las ilustraciones de los libros de historia de la antigua Mesoamérica.

Menchaca tiene una Maestría en Bellas Artes con especialidad en Grabado de la Escuela de Diseño de Rhode Island. Tiene exposiciones en todo el país y ha sido artista residente en diferentes países del mundo.

Image Gallery

English

Español

-

Engineering, technology, and great labor were needed to protect the city from periodic deluges.

Nature nurtures our communities, but it can also cause great destruction. This creek, that served as the cradle of first settlement in 1718 together with its tributary streams on San Antonio’s west side, caused heavy loss of life and property, particularly as the city grew in the 1800s and 1900s. Early efforts to remedy flooding by widening and straightening the creeks altered their age-old natural appearance but helped to control devastating flood waters. By the late 1900s, the San Antonio River Authority and United States Army Corps of Engineers determined that the most efficient and affordable way to protect downtown San Antonio from flooding would be to construct underground bypass tunnels on both the San Antonio River and San Pedro Creek.

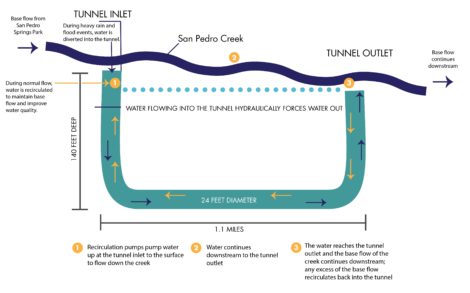

The San Pedro Creek tunnel was first to be built. Begun in 1987, the tunnel was completed in 1991. In times of deluge, raging waters enter the tunnel at the inlet shaft near here, plummet 140 feet into a 24-foot-diameter tunnel, then surge forward over a mile to an outlet at Guadalupe Street, south of downtown. Flood waters then emerge into the surface channel that courses turbulently downstream to the creek’s confluence with the San Antonio River.

Audio Tour

The flood of 1819 was enormously powerful. The governor of the time, Antonio Martinez, wrote that both the creek and river flooded, covering all of what is now downtown with water. Suddenly to those who lived and worked near the creek, it was no longer just a source of life and sustenance, but a force to be reckoned with. It was not to be trusted. And as can be expected, many people moved away from the creek to avoid further devastation. Many moved to the high east bank of the San Antonio River, now known as La Villita. Later floods, like one in 1921 that killed 51 people, led the government to make some changes. Throughout the 1900s, the creek was modified and widened to allow for more water intake. After another devastating flood occurred in 1946, the United States Army Corps of Engineers and the San Antonio River Authority partnered to implement the San Antonio River Channel Improvement Project. In the 1980s, the idea to create underground tunnels to divert overflow on both the creek and river was proposed and the San Pedro Creek project was completed in 1991.Both the San Pedro Creek and San Antonio River flood control tunnels were constructed using a boring machine or “mole.” The mole was assembled underground and bored from the outlet shaft upstream to the inlet shaft. The tunnels were lined with precast concrete panels as the mole advanced. This photograph shows the outlet shaft for the San Pedro Creek tunnel.

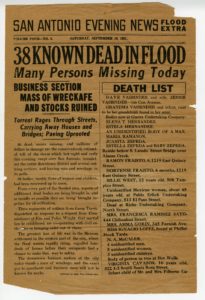

The flood of September 1921 caused significant loss of life and damage in both the downtown area and neighborhoods adjoining the river and west side creeks. Torrents of water overflowed the banks, destroying commercial buildings and washing away houses. Of the 51 confirmed deaths, all but four occurred along the San Pedro, Alazán, and other west side creeks.

The flow of San Pedro Creek remains in its surface channel under normal conditions. However in times of flooding, excess water is diverted into an underground tunnel to bypass the heavily developed downtown area. On the other hand, during dry periods when springs feeding the creek slow or cease flowing, water pumped out of the tunnel at its upstream end flows downstream through the surface channel, then returns to the tunnel at its outlet shaft to once again be recycled.

-

Una crónica de inundaciones y su legado de calamidades - La ingeniería, tecnología e intensa labor, fueron necesarios para proteger a la ciudad de inundaciones periódicas.

La naturaleza nutre a nuestras comunidades, pero también puede causar gran destrucción. Este arroyo, que sirvió como la cuna del primer asentamiento en 1718 junto con sus arroyos tributarios en el lado oeste de San Antonio, causó grandes pérdidas de vida y propiedad, particularmente cuando la ciudad creció en los años 1800 y 1900. Los primeros esfuerzos para controlar las inundaciones, que consistieron en ampliar y enderezar los arroyos, alteraron su antiguo aspecto natural pero ayudaron a controlar la devastación causada por éstas. A fines de la década de 1900, la Autoridad Fluvial del Río San Antonio y el Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército de los Estados Unidos, determinaron que la forma más eficiente y económica de proteger el centro de San Antonio de las inundaciones sería construir túneles subterráneos para desviar el agua del Río San Antonio y del Arroyo San Pedro.

El túnel del Arroyo San Pedro se construyó primero; se comenzó en 1987 y se terminó en 1991. En tiempos de inundación, las aguas furiosas ingresan al túnel por el acceso de entrada cerca de aquí, se desploman 140 pies, y luego avanzan más de una milla dentro de un túnel de 24 pies de diámetro, hasta llegar a una salida en la calle Guadalupe al sur del centro de la ciudad. Luego, las aguas de inundación emergen en un canal de superficie que fluye turbulentamente en dirección aguas abajo hasta la confluencia del Arroyo con el Río San Antonio.

Audio Guía

La inundación de 1819 fue devastadora. El gobernador de la época, Antonio Martínez, escribió que tanto el arroyo como el río se desbordaron y cubrieron todo lo que ahora está en el centro de la ciudad. Repentinamente, para quienes vivían y trabajaban cerca del arroyo, éste ya no sólo era una fuente de vida y sustento, sino una fuerza natural que se debía tener en cuenta. No era de confianza. Y como se podía esperar, mucha gente se alejó del arroyo para evitar más devastación. Muchos se trasladaron a la ribera este del Río San Antonio, más alta, ahora conocida como la Villita. Otras inundaciones posteriores, como la de 1921 que mató a 51 personas, hicieron que el gobierno realizara algunos cambios. A partir de los 1900s, el arroyo fue modificado y ampliado para aceptar más volúmenes de agua. Después de que ocurrió otra inundación devastadora en 1946, el Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército de los Estados Unidos y la Autoridad Fluvial del Río San Antonio se unieron para realizar el Proyecto de Mejoras del Canal del Río San Antonio. En los años ochenta, se propuso la idea de crear túneles para desviar el exceso de agua del arroyo y del río, y el Proyecto del Arroyo San Pedro se terminó en 1991.Tanto el arroyo San Pedro como los túneles de control de inundaciones del río San Antonio fueron construidos con una máquina para hacer túneles o “topo”. El topo fue ensamblado bajo tierra y perforó desde el pozo de salida río arriba hacia el pozo de entrada del agua. Los túneles fueron revestidos con paneles de hormigón prefabricado a medida que el topo avanzaba. Esta fotografía muestra el pozo de salida del túnel del arroyo San Pedro.

La inundación de septiembre de 1921 causó pérdidas significativas de vidas y daños en el área del centro, en barrios contiguos al río y en los arroyos del lado oeste. Torrentes de agua se desbordaron por las márgenes, destruyendo edificios comerciales y arrastrando casas. De las 51 muertes confirmadas, todas menos cuatro ocurrieron a lo largo de San Pedro, Alazán y otros arroyos del lado oeste.

En condiciones normales, el Arroyo San Pedro fluye por el canal de superficie. Sin embargo, en tiempos de inundación, el exceso de agua se desvía por un túnel subterráneo para proteger el área del centro, densamente poblada. Por otro lado, durante períodos de sequía, cuando los manantiales que alimentan el arroyo van lentos, o dejan de fluir, se bombea el agua del túnel a lo extremo de aguas arriba para que fluya aguas abajo a través del canal de superficie; y posteriormente regresa al túnel en su acceso de salida para reciclarse nuevamente.